When reviewing the kettlebell swing people usually tell you what not to do and give various examples of bad form. What you rarely hear are the precursors that define a good kettlebell swing and why –

- Safety – Unless your form is mechanically insane it is actually quite difficult to do a “very bad” swing. The 2 culprits would be wild hyperextension at the end of the concentric phase and thoracic flexion into a sudden drop and jack-knife action at the hip complex; which could put some unwanted mobility in your lumbar discs.

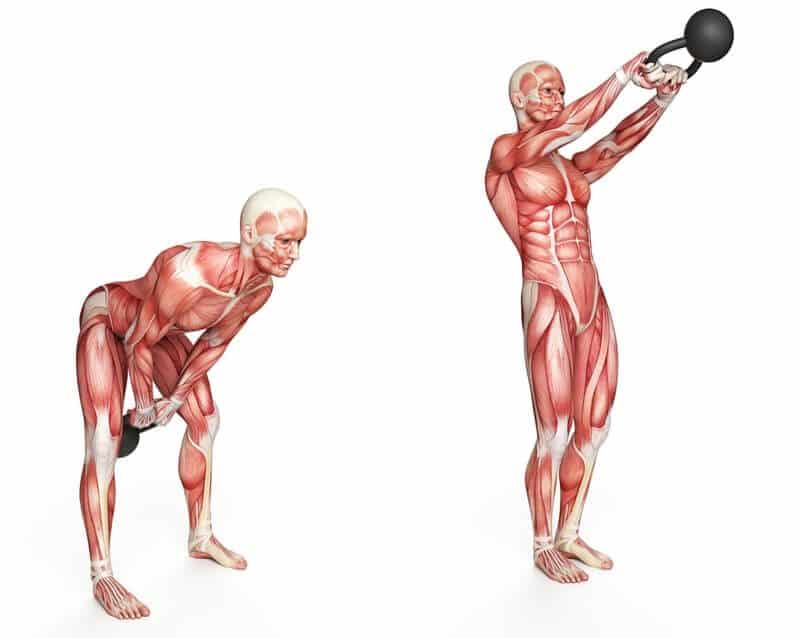

The hyperextension here is not excessive and certainly not life-threatening based on the weight. Something to be mindful of for good form though.

While the end phase should see the kettlebell facing away based on power and velocity, the loading phase here is quite bad with a huge degree of hip flexion resulting in the shoulder coming below the hips.

- Purpose – while safety is paramount with any form of physical activity and most things in everyday life, purpose is the one that is often overlooked. The inclusion of kettlebells into a routine should be for a specific purpose unless the goal is just general fitness. When understood properly they have a huge potential for athletic performance, injury rehabilitation and very high levels of fitness.

To address safety we need to look at the correct mechanics and loading of the swing throughout the complete range of motion and consider where problems can arise in order to be aware of these and avoid them.

The best way to understand the movement arc and range of motion for the kettlebell swing is that of a pendulum. Even better is the use of a Newton Cradle or a child’s playground swing. The first part to address is the contribution of vertical and horizontal forces. For a lot of coaches and kettlebell lifters the interpretation of what they see, dictates how they do it. To the observer, a kettlebell swing sees the object move from around knee height on the back swing to around head height on the forward swing. The displacement and range the object has travelled is several feet in the vertical plane. This would translate into a squatting based movement to achieve the height required to finish a good repetition. The usual result in technique from this is the hips stay over the base of support and the knees bend outside of it and ahead of the body. While it is not wrong, and certainly not dangerous, it is just not efficient in time or motion as we will see.

Both Newton’s Cradle and a swing perfectly demonstrate the rang of motion involved in the kettlebell swing and therefore the mechanical loading properties required to produce those movements efficiently.

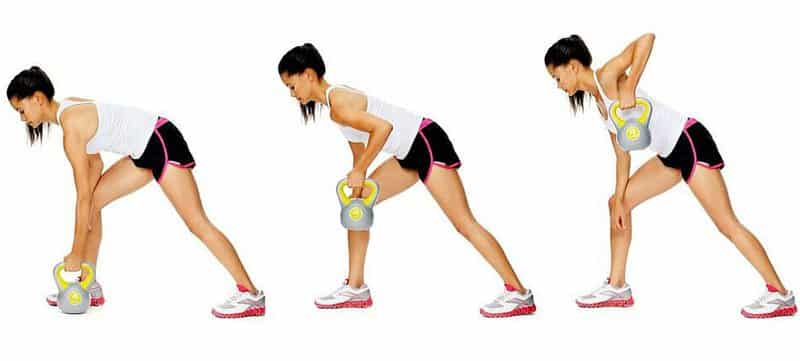

If you stay partially upright and bend the knees to generate force it is very difficult to get the kettlebell behind you as the arms are blocked by the legs. This is an extremely important consideration for efficiency as returning to the analogy of a pendulum we have a problem. When a knee dominant squat with a relatively upright torso stops the kettlebell from travelling behind the lifter the entire benefit of potential energy has gone and the lifter requires more effort. Consider Newton’s Cradle in the image above. The further the first ball is pulled from the group, the greater motion it causes to the last ball at the opposite end of the cradle. With cause and affect we have an action causing a reaction that is directly related to the magnitude of the action. The same is true of the kettlebell swing. When the kettlebell is allowed to travel behind the lifter it now has potential energy at the end of the eccentric phase, just before it begins to move forwards. This would be known as the transition where it is almost motion free for a split second. During travel it would have kinetic energy.

If Newton does not work for you then a child’s swing will. When you pull the swing back and let go the achieved forward motion is very slightly less that the movement away from equilibrium. For example, pull the swing back 30 degrees and it will probably swing forwards 28 degrees, then back to 26 degrees, forward to 25 degrees and repeat this very gradual loss of energy until once again reaching equilibrium and coming to rest. This is an important consideration for the kettlebell lifter as if there is no backswing you basically have no potential energy (apart from dropping it and using gravity) and have to start the upward phase of the lift with extra effort; usually shoulders and hyperextension – like pushing a stationary car compared to one already moving very slowly. To take the analogy of the child’s swing a stage further the action required to initiate movement is also very relevant. When mentioned above that people often mistake the vertical height achieved as an indication that a strong vertical, or squatting, component must be present, consider how the child’s swing is initiated. Invariably people push forwards to achieve the vertical height and this translates extremely well to the kettlebell swing and the use of horizontal force.

Here we see 2 examples of eccentric loading based on excessive knee flexion resulting in the kettlebell being very close to equilibrium. This results in a squat action being required to initiate the movement with almost no potential energy.

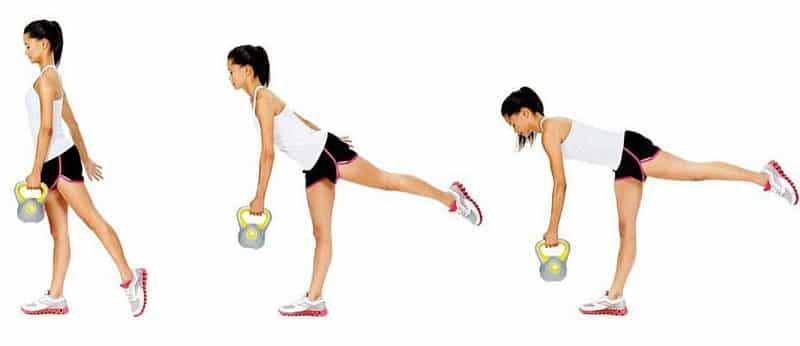

Firstly, we need to understand how to effectively initiate movement that will produce the desired force to move the kettlebell through a fixed pendulum arc. If you stand up and bend your knees forwards so they go over your toes, this is the squat swing we referred to above and not ideal. Now keep the knees exactly where they are and fold at the hips so that the backside moves way behind your base of support. The aim is to fold at the hips as this gives us 3 great advantages –

- We have efficiently loaded the posterior chain for powerful horizontal forces based on hip flexion.

- We have allowed the kettlebell to travel under and behind us to efficiently utilise potential energy many degrees from equilibrium.

- 30% of the lift has already been done as the kettlebell will swing to stomach height based on the laws of physics and pendulum motion. We just stand with varying speeds to dictate how much power assists in the lift.

Now to cover the correct loading for the swing. After teaching kettlebells for far too long, one day a completely new way of explaining things flew in from somewhere and seemed to work better than anything before. We have told people to fold, hinge, think of a bow and arrow, compare vertical jump and horizontal jump preparation to understand the mechanical loading differences and then all of that was thrown away and conveniently replaced with this.

- Stand with your back to the wall

- Take half a step forwards

- Sit back so your backside touches the wall

You have just loaded the posterior chain in the perfect anatomical position to swing a kettlebell.

As you can see from above the legs remain almost straight with minimal knee flexion. This allows for a powerful loading of the posterior chain to catapult the weight forwards. More importantly, potential energy would cause the kettlebell to swing to at least the blue kettlebell and possibly the grey one if the lifter paused in this position and did not extend – just allowing the weight to move along a fixed path. This efficient use of potential energy assists in posterior loading and also in making every rep less effort for work capacity in time.

The next thing I am sure you are burning to find out is how high to swing the kettlebell? That is quite simple as well.

- If it weighs nearly as much as you – hip height

- If you want maximum carry over to athletic performance and kettlebell competitions then between chest/shoulder/ head height.

- If you compete in crossfit competition then you have to go overhead, but not all the time.

The overhead swing has been done to death on many fronts; mainly injury, silliness and red-faced angry bird coaches who hate lots of things. We took the more diplomatic approach having worked extensively with the crossfit community and gave you a complete overview below –

Click the image above the the overhead swing article.

From this loaded position where we are predominantly in hip flexion with the posterior chain loaded and ready to spring, the next phase of movement is to reverse the hip hinge and open to stand tall. It is a fixed and repetitive pattern and the key coaching focus should be on directing a majority of the work to the hip complex.

Now we can do it, what do we do with it?

Good question – time for the purpose!

Kettlebells are not usually a training tool that fits into the general variable manipulation of most periodised programs. Rarely do you see 4 sets of 12, or 5 sets of 8-10 for any of the exercises or workouts. From experience, much of the training is for work capacity in time. This is either replicating the specific timed demands of kettlebell competition, or just because lifters seem to favour getting a good workout in a short time period. While an hour in the gym can sail by, an hour with kettlebells is enough for 2-3 training sessions.

If we specifically focus on the swing and successful integration into programs then a few things have to be considered in order to benefit from the inclusion. The swing works around 80% of the muscles in the body from eccentric, concentric and isometric and trains peripheral heart rate to a high degree demanding blood supply to the upper and lower extremities throughout the active training phases. This is why extremely fit people usually burn out after a few minutes of swings – the body is simply not used to training at this intensity and with this much active muscle engagement over a prolonged time period. People have called it the cardio equivalent of quicksand – the breathing gets out of control and you begin to melt like a candle.

Swing planning can take many forms and is not limited to the following variables –

30/30 – 30 seconds active and 30 seconds rest for a fixed time – 5-10 minutes for beginners.

30/30 where rest now becomes active and can range from mobility to star jumps and burpees.

60/30 a 2:1 ratio promoting fatigue resistance and a greater VO2 demand

Alternate swings – changing hands every 30 – 60 seconds for a fixed time

Complexes where swings are combined with additional kettlebell exercises or calisthenics. A great one here is the press up as the main non movers in the swing are the chest and triceps and these are prime movers for the press up to give a fuller workout.

Kettlebell swings are also a fantastic way to prepare for conventional weightlifting and powerlifting sessions. Research by Professor Stuart McGill has shown that the swing opposes the lumbar shear forces of deadlifts and so would be a great post workout inclusion after them. Based on the flexion and extension patterns the swing is also good as a warm up tool for Olympic weightlifting where very similar eccentric loading and concentric force production is observed. Incidentally, the official kettlebell sport competitive events are snatch and clean and jerk.

The kettlebell swing can give you a lifetime of health and fitness once you can perform it safely.